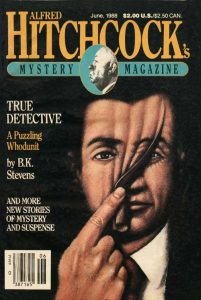

Excerpt from B.K. Stevens’ interview from The Digest Enthusiast book six:

TDE: How did the Lt. Johnson and Sgt. Bolt series develop, and why did you choose to tell the stories as letters?

BKS: Believe it or not, the premise for the Walt Johnson and Gordon Bolt series came to me in a dream. I’d been writing mysteries for two or three years, without coming up with anything publishable, when I woke up one morning with a vivid impression of a scene. Two police detectives are walking across the grounds of a large estate, talking. The first detective says, “It was a clever murder, wasn’t it?” The second replies, “Not so very clever—unless you mean the part about the horse.” The first detective is utterly confused—it had never occurred to him that a horse might be involved. “What horse?” he demands. The second detective misinterprets his question and says, “Does it matter what horse? One from the stables, I suppose.”

That sliver of conversation defined the characters of Walt and Bolt, established the relationship between them, and set the pattern for every story in the series. Walt Johnson is a highly respected police lieutenant. Everyone, especially his adoring subordinate, Sergeant Gordon Bolt, sees him as a brilliant detective. But Walt is in fact a dim bulb, earnest and well-meaning but always in a fog. He blunders through his cases, missing every clue, blurting out clichés and irrelevant observations that reveal just how lost he is. Bolt, much smarter than Walt but far too humble, thinks Walt is a genius and seizes on everything he says, misinterpreting all his muddle-headed remarks as dazzling deductions. Bolt’s the true detective. He’s always the one who figures everything out, and Walt’s always the one who gets the credit. Walt feels guilty about it but lacks the courage to admit the truth to anyone, including Bolt. That’s the basic plot for all twelve Bolt and Walt stories.

As for the letter-writing form of the stories, I read several epistolary novels in graduate school, including Samuel Richardson’s Pamela and Clarissa—I didn’t love the novels, but I was intrigued by the form. (And I relished Henry Fielding’s epistolary parody of Richardson, Shamela.) I also read Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone, an early mystery and a variation on epistolary form, and I was struck by Jane Austen’s use of long letters in novels such as Pride and Prejudice. When I gobbled up Dorothy Sayers’ works, I liked her use of epistolary form in “The Documents in the Case,” a long short story she wrote with Robert Eustace. So when I cast about for a way to tell Walt’s story, epistolary form occurred to me as a possibility. Walt is plagued by guilt because he’s become a success by taking credit for Bolt’s accomplishments. He needs to confess, and to whom should he confess if not to his mother? In the third story in the series, “True Romance,” Walt’s widowed mother emerges from the letters when she pays Walt a long visit and wins the heart of Sergeant Bolt. That story is told in the form of a long letter from Walt to his ever-patient wife, Ellen. Of course, Walt has no idea that his mother and Bolt have fallen in love, just as he has no idea of what’s going on in the case he and Bolt are investigating; readers have all the evidence they need to realize the truest romance in “True Romance” is the blossoming one between Bolt and Mrs. Johnson, but Walt never suspects. All the other stories, as I recall, are written as letters from Walt to his mother—except that by the eleventh story, “True Test,” Walt has switched to e-mail, and breaks off suddenly when Ellen goes into labor with their second child. The final story, “True Enough,” is a letter Walt writes to his mother while she and Bolt are on their honeymoon.

Comments are closed.