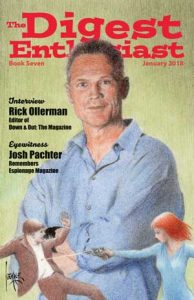

Excerpts from the interview with Rick Ollerman, editor of Down & Out: The Magazine, appearing in The Digest Enthusiast No. 7.

Excerpts from the interview with Rick Ollerman, editor of Down & Out: The Magazine, appearing in The Digest Enthusiast No. 7.

TDE: What are the core elements of The Magazine?

RO: I knew that I wanted to cross-pollinate fanbases as much as I could, and to promote the authors and their stories—especially when they write a story with their series’ characters—as much as their own fanbases would support the magazine.

Another was kind of the unspoken notion of size; we just sort of knew it should be a digest-sized magazine without ever really talking about it.

Another thing I want to do that many new magazines in the POD era don’t do is offer subscriptions, something we will definitely do, probably starting with the second issue.

We’ve also got a non-fiction column by J. Kingston Pierce, who used to write for Kirkus Reviews before they reshuffled.

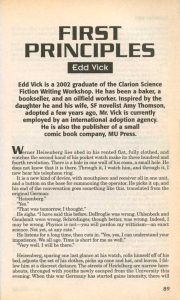

Another hopefully unique feature answers that burning question you never knew you wanted to ask: what happened to short crime fiction after Hammett and Chandler left the pulps for the slicks and nov- els and Hollywood? Obviously, the pulps kept going, but who kept them going with the two big stars gone?

The page count is right around 170 for the first issue. I think we’ll wait on reader response to see if that moves, and by how much.