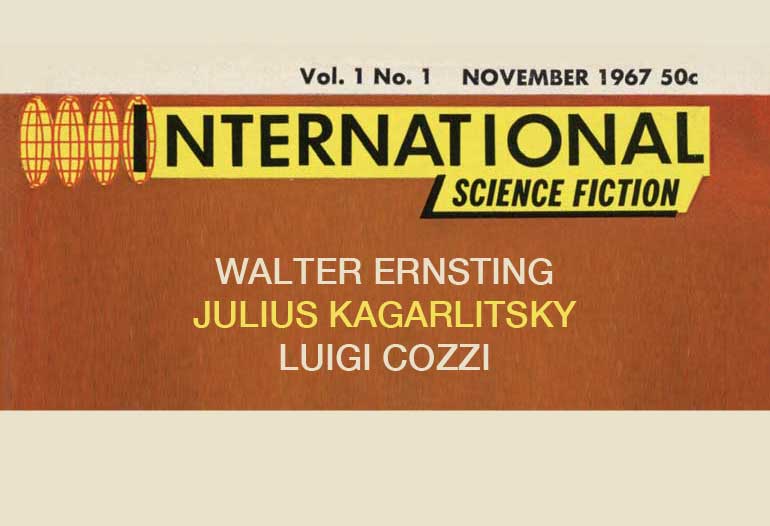

The second feature in International Science Fiction Vol. 1 No. 1 (Nov. 1967) is a trio of reports on the state of “Science Fiction Around the World.” Walter Ernsting begins from Germany, where he reports, “After the second world war a new kind of sf became popular: modern science fiction as you know it in America and England.”

The second feature in International Science Fiction Vol. 1 No. 1 (Nov. 1967) is a trio of reports on the state of “Science Fiction Around the World.” Walter Ernsting begins from Germany, where he reports, “After the second world war a new kind of sf became popular: modern science fiction as you know it in America and England.”

Walter Ernsting (1920–2005), who wrote under a pen name Clark Darlton, chosen by a German publisher, authored hundreds of novels, but only a few were published in the US—a few years after ISF ended.

“In 1961 some writers put their heads together, and three months later the most famous serial of the world was born: Perry Rhodan, with an edition of 200,000 copies weekly. Just now number 300 is on the newsstands.”

The writers were Ernsting and Karl-Herbert Scheer.

Perry Rhodan was quickly picked up by Ace Books in the US where 126 novels were published from 1969 through 1978. Another 19 were published independently by translator Wendayne Ackerman (wife of Forrest J. Ackerman) as Master Publications.

“Science fiction has its boom in Germany now. The Moewig-Verlag in Munich presents twenty titles every month; it is really the biggest sf publisher in the world. The agency Panorama in Vienna is the agent for most of the German authors.

Ernsting’s connection with Galaxy is also mentioned. He edited the German Galaxy paperback series that ran for 14 editions, the last five with co-editor Thomas Schlück, from 1965 to 1970.

Julius Kagarlitsky’s report from The Soviet Union is translated by Anne McCaffrey and Irina Poutiatine.

“The young writers in the late 50’s overwhelmingly desired to tell what Science is going to give the world . . . Now, however, Soviet sf is being judged solely as science-fiction literature which is devoting itself, above all else, to the questions of the social and psychological consequences of scientific and technical progress.”

He highlights the work of two writing teams—Mikhail Emtsov and E. Parnov; and brothers Arcady and Boris Strugatsky—in particular the former team’s novel Soul of the World.

“In America, many short stories are written; we write very few. Most of our science fiction writers lean toward the novel and the novelette.”

Luigi Cozzi reports from Italy. He begins with April 1952 when the first Italian science fiction magazine was launched. Scienza Fantastica lasted only seven issues, but was followed that same year by the bi-weekly Urania, which featured novels. Leveraging reprints of the best American SF novels, Urania soon reached average sales of 50,000 copies. But by the late 1960s, as sales of hardcover SF titles climbed, the magazine’s circulation dropped to about 20,000 copies an issue.

“You must consider that the Italians mean by “magazine” what the Americans usually call a ‘pocketbook.’ All Italian science-fiction “magazines” are pocketbooks featuring the cover novel, a serial (which is a short novel shared into an unbearable ten or fifteen parts) and some advertising and comics.”

Cozzi mentions several writers, but they seem to come and go, as do the dedicated science fiction magazines. He concludes by observing, “The good Italian science-fiction writers are rather few.”

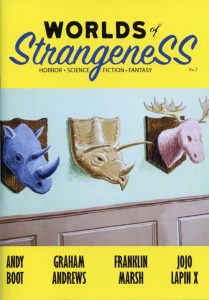

Nigel Taylor’s World of StrangeneSS is an annual, self-published digest that has appeared round about Halloween since it began in 2016. Its first two issues were printed traditionally, but fellow Brit Justin Marriott’s successful switch to POD with the Paperback Fanatic line of zines has not gone unnoticed at WOS HQ.

Nigel Taylor’s World of StrangeneSS is an annual, self-published digest that has appeared round about Halloween since it began in 2016. Its first two issues were printed traditionally, but fellow Brit Justin Marriott’s successful switch to POD with the Paperback Fanatic line of zines has not gone unnoticed at WOS HQ.

Weirdbook

Weirdbook

The final story of

The final story of

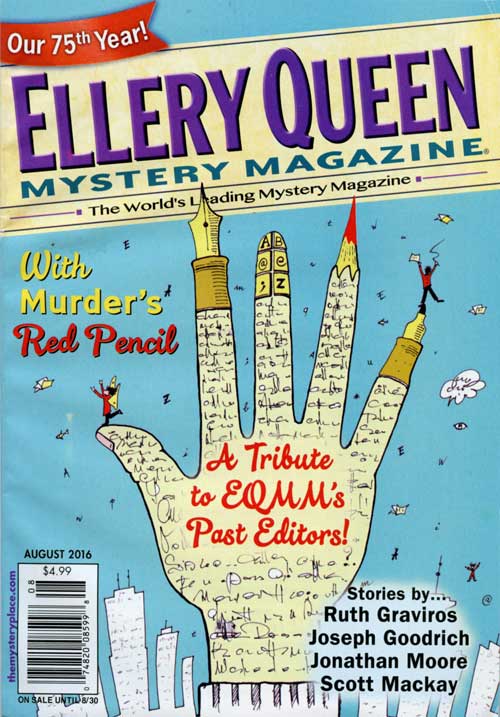

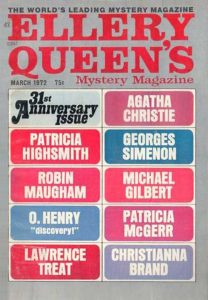

From the Potpourri section of

From the Potpourri section of

From the Potpourri section of

From the Potpourri section of

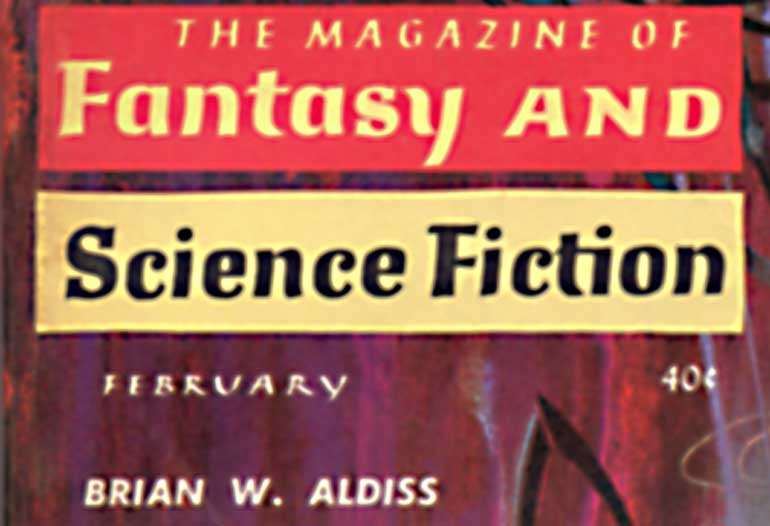

Excerpt from Joe Wehrle, Jr.’s review of the Hothouse series by Brian Aldiss, from

Excerpt from Joe Wehrle, Jr.’s review of the Hothouse series by Brian Aldiss, from

From the Potpourri section of

From the Potpourri section of

The second feature in International Science Fiction Vol. 1 No. 1 (Nov. 1967) is a trio of reports on the state of “Science Fiction Around the World.” Walter Ernsting begins from Germany, where he reports, “After the second world war a new kind of sf became popular: modern science fiction as you know it in America and England.”

The second feature in International Science Fiction Vol. 1 No. 1 (Nov. 1967) is a trio of reports on the state of “Science Fiction Around the World.” Walter Ernsting begins from Germany, where he reports, “After the second world war a new kind of sf became popular: modern science fiction as you know it in America and England.”

From the Potpourri section of

From the Potpourri section of

The first story in International Science Fiction No. 1 (Nov. 1967) is from The U.S.S.R, “Wanderers and Travellers” by Arkady Strugatsky.

The first story in International Science Fiction No. 1 (Nov. 1967) is from The U.S.S.R, “Wanderers and Travellers” by Arkady Strugatsky.